The ClimOP project aims at identifying and supporting the implementation of operational improvements (OIs) to reduce the climate impact of the aviation sector. To this end, the stakeholder engagement helps define a suitable set of actions and advice to foster the application of the most promising environmental mitigation strategies by policymakers.

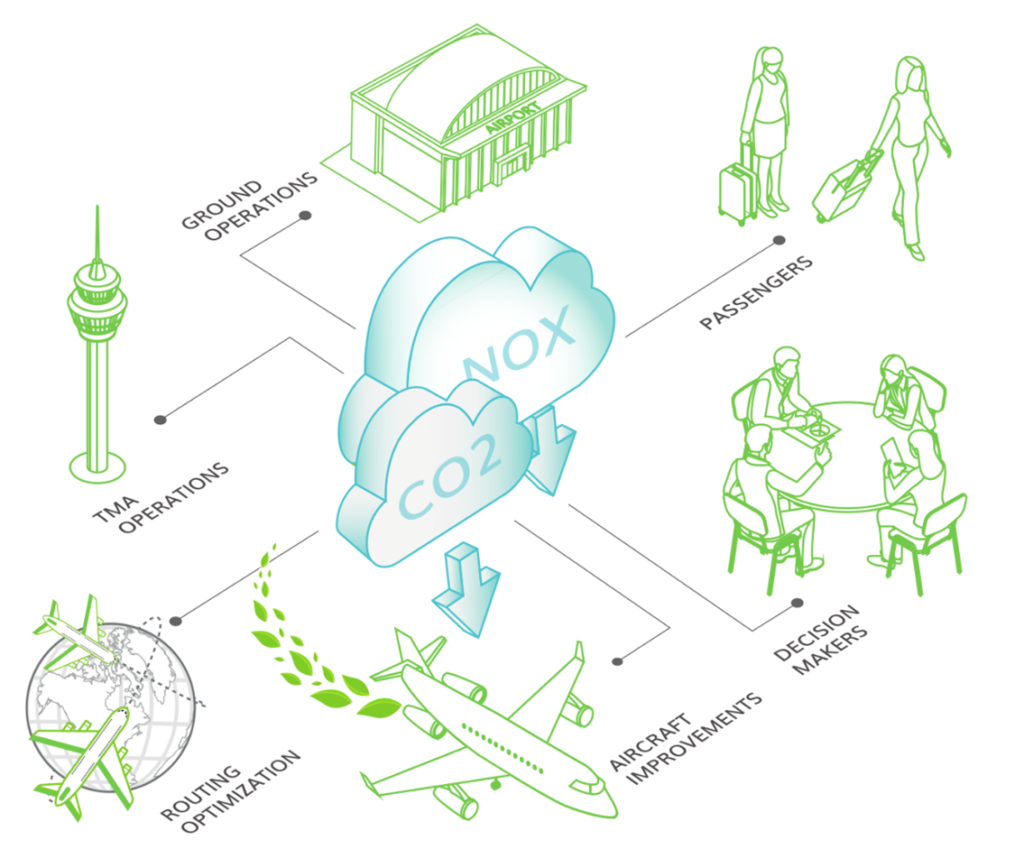

In its first ten months, ClimOP identified a wide range of operations that can reduce the climate impact of aviation. These operations can be categorised according to the following areas (Figure 1):

- Operations on the ground;

- Operations in the Terminal Manoeuvring Area (TMA);

- Airline network and in-flight operations;

- Operations at a regulatory level.

Figure 1. ClimOP’s Stakeholders and Operations

Each operational area involves multiple stakeholders that, in general, are impacted by the introduction of a new or modified operation. Therefore, when the first set of operational improvements and key performance indicators were identified, the project Consortium hosted an online workshop with representatives of airlines, airports, Air Navigation Service Providers, passengers, researchers, and aerospace manufactures.

The goal of the meeting was to discuss with the stakeholders what understanding they have of the selected operational improvements, and to collect their opinions on their feasibility and likely consequences. The workshop was the first step of ClimOP’s stakeholder engagement plan. In fact, ClimOP plans to involve stakeholders in a continuous discussion to ensure the project focuses on operational improvements applicable to real-life situations and with an actual impact on climate change.

Flying lower and slower

For example, “Flying low and slow” is one of the operational improvements selected by ClimOP. It exemplifies the implications an OI can have on climate and on the involved stakeholders.

Currently, the typical cruise-phase altitude of most aircraft is at about 36,000 feet. In this region of the atmosphere (the tropopause), the emission of NOX and other non-CO2 species has the maximum negative impact on climate.

A systematic reduction of the cruise altitude, for example to 28,000 feet, can significantly lessen this impact¹ ². However, a higher altitude is where the fleet presently in operation has the optimum fuel performance. Consequently, flying under off-design conditions will cause additional fuel burning and thus more emissions. Therefore, the net effect of “Flying low and slow” has yet to be determined.

Figure 2. Air traffic controllers at work

Stakeholders’ impact of slower and lower flights

The introduction of this OI has different implications on the involved stakeholders, namely airspace users, passengers, and air traffic controllers. The former will incur in higher operative costs because of the increased fuel consumption. These additional costs will probably translate into more expensive flight tickets, thus affecting passengers. “Flying slower” will affect passengers also by determining longer flight times, with potentially negative consequences in case of multi-leg flights.

Another effect to take into account is that on network operations. A new way to accommodate all flights within a fixed maximum altitude will have to be found. Consequently, there will be a higher density of en-route aircraft with a likely increase in the workload of air traffic controllers (ATCs) and pilots. Indeed, if the available airspace becomes more crowded than it currently is, ATCs and pilots will probably have to perform a higher number of actions per flight to guarantee that the standards of safety are met, for example the minimum horizontal and vertical separations between two airplanes at any given time.

Figure 3. Human Factors specialists dealing with the validation of a project’s results

Shaping a human-tailored future

Leading the development of the climate optimized mitigation strategies is Deep Blue, a research and consultancy Italian SME specialised in human factors. Deep Blue aims at bridging the gap between the research activities and the implementation of the project results in real-life situations. This Italian company operates in contexts with high safety, security and resilience requirements, such as Transport, Healthcare, Energy and Manufacturing. In these areas, and thanks also to its past role in large EU-funded projects as an expert for the validation of operational concepts and as communication leader, Deep Blue leveraged its ability at developing user-centred solutions focused on stakeholders’ needs.

The expertise of Deep Blue

For several years, Deep Blue based its work on the identification of the stakeholders’ pain points to develop advanced technologies able to improve human performance. In the NINA project, for example, Deep Blue identified a set of indicators for the cognitive workload that an automated system would have used to allow Air Traffic Managers to operate safely. In the ACROSS project, instead, Deep Blue assessed and employed pilots’ needs to design a cockpit able to reduce the workload in two-pilots operations. Finally, in the INDIMO project Deep Blue is working to provide digital solutions that increase the accessibility of public transportation for people who face barriers.

But Deep Blue does not apply its human-centred approach only to research activities. Indeed, while operating in European research projects, this Italian small giant also supports enterprises and international institutions (e.g World Food Program, Tetra Pack, IATA, Leonardo, Eni, EUROCONTROL, …) with courses and consultancy services for the integration of new operations in their work environment.

With its consultancy, Deep Blue offers tailored training solutions to develop the soft skills of ATCs and pilots, teaching them how to deal with work-related stress factors by developing their emotional intelligence, conflict management and communication skills. Deep Blue also delivers safety assessments of work environments, and trains employees to prevent dangerous situations by recognizing potential threats.

Do you want to know more about Deep Blue? Go visit their website.

¹ C. Frömming, M. Ponater, K. Dahlmann, V. Grewe, D. S. Lee, and R. Sausen, “Aviation-induced radiative forcing and surface temperature change in dependency of the emission altitude,” J. Geophys. Res., vol. 117, no. D19104, 2012, doi:10.1029/2012JD018204.

² V. Grewe and A. Stenke, “AirClim: An efficient tool for climate evaluation of aircraft technology,” Atmos. Chem. Phys., vol. 8, no. 16, pp. 4621–4639, 2008.